The dynamics and opportunities for development and transformation of groups

Written by Peter Schlichting Mortensen, relead.dk

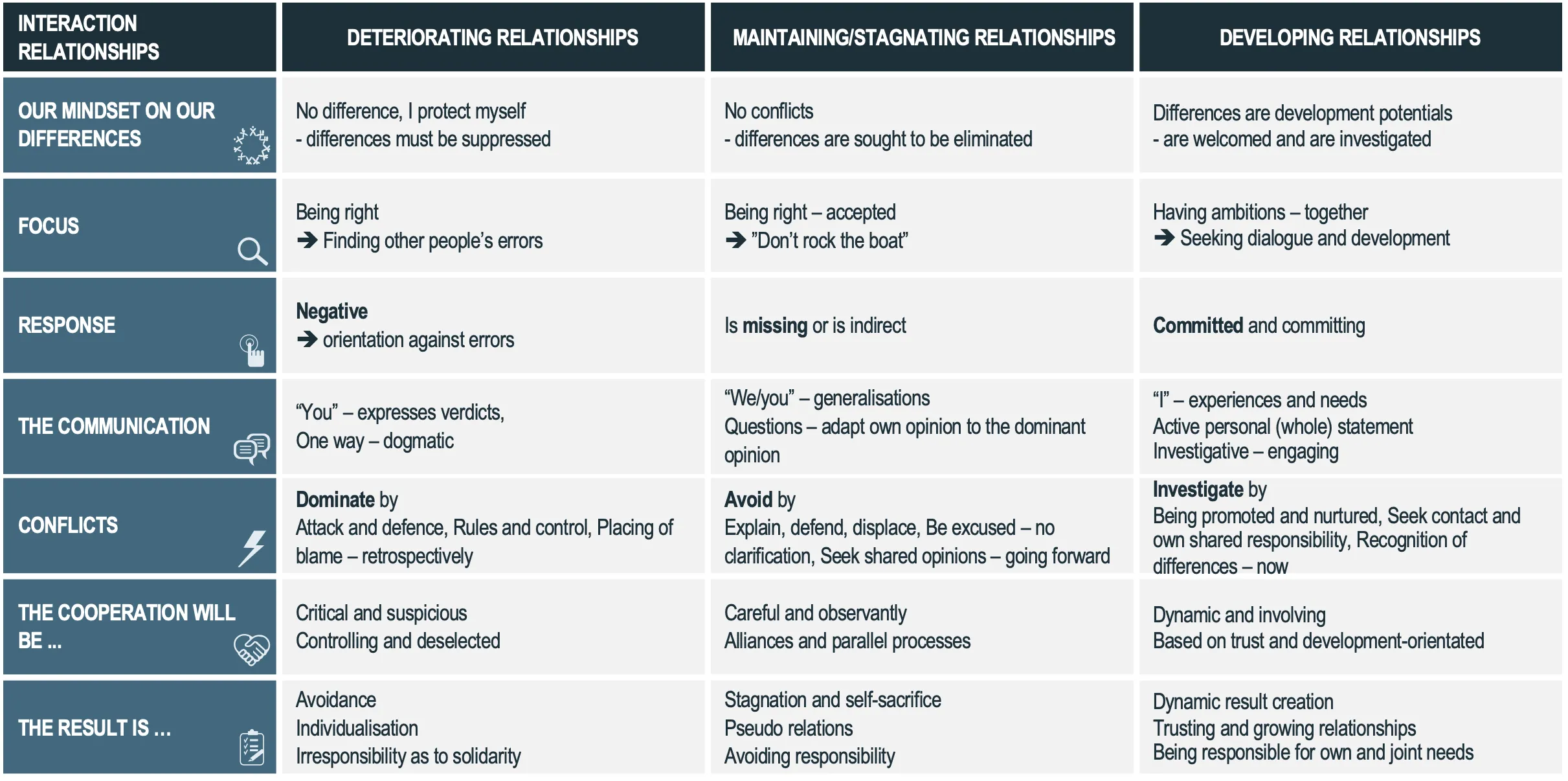

All interhuman interaction processes might lead to stagnation, deterioration or development. This is true in all relations: at work, in your professional relationship, in your private relationship to friends, families, etc.

Healthy group dynamics and good collegial relationships are crucial in keeping employees’ and leaders’ zest and for them to feel that they are growing and developing from the tasks they are handling. In addition, this is what creates the real cohesive force in a group.

What is true however for many is, that the collaboration does not develop. Content and life are sucked out of the collegial relations and thus become more limiting than rewarding.

For others, the adverse or dysfunctional interactions and relationships become direct strains on the individual’s well-being.

In both instances, it is a high price to pay for entering into cooperation and being part of a group.

In my experience, all groups can develop, and the dynamics in relations can mature and unfold more of their potentials.

Focused efforts are needed to create development. In particular, it requires a confrontation with the common understanding that cooperation and working environment evolve spontaneously, and it is therefore perceived as a basic condition you have to live with without having any personal, direct or concrete influence on it.

The first step in developing and improving a group’s climate is for the group to decide on a form of self-scrutiny and to identify the patterns and dynamics in the group. The group’s dynamics are rooted in specific interactions between individuals, and it is therefore not only the group’s patterns that have to be identified and taken responsibility for, but also the individual’s contributions to the patterns.

Some of the typical dynamics that characterise stagnating, deteriorating and developing groups are described in this text. How groups can turn stagnation or setbacks to renewed development will be described as well.

Maintaining and stagnating dynamic

All groups establish some routines and patterns that maintain the group’s functions, dynamics and self-perception or identity.

On the one hand, routines and habits create security so that you do not have to constantly invent everything from scratch or come up with all solutions and decide everything yourselves.

On the other hand, habits and routines will eventually lead to less flexibility and awareness. The force of habit strikes, and the habits become indisputable and only worth preserving because “it has always been like that”.

Routines carry the inherent risk of comfort and somnolence. You do not consider or notice whether the routines still fit you or whether you have just adapted to the routines. This also applies to the roles and dynamics established in the interaction between colleagues and the interaction with management.

Overall, it creates limitations as to creativity, innovation and development, i.e. it slowly grinds any development to a halt.

All groups will experience periods where habits become adverse. They do not match the members’ resources and differences any more or the tasks or expectations from the surrounding society to the organisation. It is not an issue in itself that development comes to a standstill or that the habits become limitations for a while. The important thing is how this is met by leaders and the individual team member, and the group’s collaborative competences will be crucial.

The group might take on the task to re-orient itself and create development or it might continue the patterns leading it to the current situation. If the group keeps the patterns, it might move from bad to worse, i.e. the group moves from being maintaining to being stagnating.

Stagnation occurs when no one succeeds in challenging the habits and breaking the patterns.

We all have an inherent willingness to show consideration and be forgiving which is a major help in everyday life. We are also to varying degrees inclined to be evasive, avoid any hassle, hope for the best and think: maybe, it is just me or why should I do it? When thoughtfulness becomes avoidance or evasion, a pattern is created which will impact the entire group’s level of function.

The group’s dynamics will in itself subdue innovation by e.g. reducing differences or appealing to common opinions not being shared. Agreement or consensus becomes a restrictive ideal and not a consequence of developing dialogues clarifying differences and creating a foundation for a truly shared understanding.

Conflicts are considered possible to avoid if everyone makes an effort. Conflicts are usually trivialised for as long as possible. Conflict solutions are often quick settlements trying to find compromises and reconciliation instead of investigating the actual existing differences. It is often said that you have put the conflicts behind you, however, they are often lingering in the shadows and will eventually swallow you up.

The ones sticking their necks out by being challenging or critical might be looked upon as unsatisfied, difficult or disloyal. Even though they might have colleagues who support them in the wings and who will in some way benefit from what is said, they might easily find themselves in a marginalised position in the group. They might rightfully feel walked out on by their colleagues because they only support them in the wings.

Response in these groups is often non-existent or vague, i.e. impersonal and of such overall character that it does not make any difference for either the sender or the receiver. It is more important to confirm each other than to dare to challenge and investigate. The unsaid is piling up and becomes moods which might be notable but difficult for everyone to relate to.

This often results in the fact that many feels left in some sort of a vacuum where they do not know how they contribute, are perceived or how they affect their colleagues. This applies to both leaders and employees and often leads to unnecessary insecurity and anxiety about the value of your work and existence in the group.

Curiosity falls, and comfort gets the upper hand. The expectant involvement many experiences at the beginning of a new work relationship is replaced by modesty or resigned acceptance. The group’s overall energy level drops and the overall shared understanding will be that “the effort is not worth the expense”. Meetings will e.g. become detached and marked by a lack of participation, either physically or mentally. Or the old guard will show its face, i.e. the same persons will perform the same tasks and often in the same ways as many times before, and it can therefore not go completely wrong. Paradoxically, the old guard might hinder new colleagues from entering the scene by signalling that the tasks are best accomplished as always, and the new colleagues might therefore doubt their abilities to be able to do it in a satisfactorily way.

In short, the group’s level of ambition might then just be that we only have to get by as easily as possible, and why “rock the boat”?

The difference, which is still there, and which will never disappear mostly appears in subgroups. Your opinions will be confirmed here through interchanges with like-minded, but they will however not be tested or challenged in the bigger group.

Whether it is individuals or subgroups which hold back ideas and opinions, it will result in the fact that the entire community loses knowledge, energy, initiative and belief in what can be achieved. The community’s or the group’s part of this dynamic is that it does not actively seek other points of view than the already existing ones.

The hope for change is often directed at management because the individual employee feels a lack of initiative or power of penetration. Any initiatives must come from them because it is management’s responsibility to ensure development and new initiatives. The manager might find himself alone with responsibility, miss being challenged or being able to spar with the team members. Both parties are right, however, none of them succeeds in creating the necessary change in the underlying dynamics.

If you are to talk about a cohesive force in these groups, it often rests on stories about earlier times, and it thereby sustains a nostalgic or retrospective self-understanding.

Groups which discover that they have become stagnating have a choice. They can start a development process, which e.g. can be initiated by a group check. It is a group check, a workshop, which focuses on habits, social conventions, roles and patterns and what they mean to the individual’s well-being and development as well as the effect on the group’s overall level of function. For the process to make sense and lead to change, all group members have to participate as well as the closest manager(s). More and more companies choose to have recurring group checks, where the development efforts, or lack hereof are supervised and supported.

The process is to a high degree a question of confronting your own comfort or willingness to do nothing instead of standing out. Everyone will see where he/she has become less careful, engaged or contributory and take own responsibility for reversing that development. It is of course also about seeing the need to review meeting structures, information flows, decision processes and similar of a more organisational nature.

If nothing happens, the group might enter a downward spiral which leads to what I call ´deteriorating´.

Deteriorating group dynamic

Deteriorating dynamics have many costs, and the word “deteriorated” is to be taken in its literal sense. The employees’ and managers’ belief in themselves as specialists, colleagues and in worst case humans is being deteriorated or broken down. Stagnation comes from comfort; however, deterioration is being created by fighting for survival in the group or at the workplace.

The group’s workdays are filled with non-constructive conflicts and power struggles. It results in loss of involvement, creativity and loyalty or the feeling of belonging to the group. A direct consequence is job dissatisfaction, absence due to sickness, exodus of staff and poor work quality.

Another significant loss is the loss of self-respect as a result of seeing yourself falling into responsive patterns or social conventions, which you did not have before. We all resort to certain ways when we are under pressure and fighting to care for ourselves. Defence patterns take over, it feels insecure to show confidence in others, and you find yourself seeking alliances instead of functioning freely with everybody. No one wants that, but only a few will be able to keep clear of contributing to this downward spiral.

One of the characteristics of these groups is a distinct fault-finding culture. There is no room for experiments or making mistakes, and mistakes are often pointed out in disrespectful or intimidating ways and more often than not in front of others. A custom which for sure has an intimidating effect on everyone witnessing it. It results in growing insecurity and vigilance, which easily lead to everyone watching each other and perhaps especially for other’s mistakes and without wanting to thereby contribute to reinforcing the pattern.

Acknowledgement is rare and often comes in the misunderstood form as praise. Praise and blame are two sides of the same coin. Both imply an assessment and thus also that you are being assessed instead of being seen on your own terms.

When there is no acknowledgement, many of us are inclined to concentrate on getting praise. The problem is that they will to a higher degree be inclined to do what they hope is correct in the other group members’ eyes, instead of what they can vouch for and take ownership of. Consequently, it weakens creativity and self-responsibility. As the level of self-responsibility disappears, management often steps in with more control and monitoring in an even more self-reinforcing pattern. The more control from the outside, the more people feel under suspicion and underestimated fuelling a smouldering dissatisfaction or direct opposition against e.g., leaders or their decisions.

Reciprocity exists in all patterns. The staff can ask for praise, and the management can see themselves as the one or the ones who have to assess and qualify the value of others’ efforts. It is a powerful position which can be difficult to let go of even though it creates an adverse dynamic between the leader and team members.

The lack of reciprocity which the above expresses is reflected in many ways.

Due to the amount of criticism and low tolerance towards mistakes, it becomes more important to be right and stand firm than to doubt and urge dialogue.

The form of communication becomes self-opinionated, commanding or generalising. It defines others and lacks self-reflection and it does not consider how it is received or how it affects the recipients.

It is all about taking a message and do what is asked. This is what is considered as loyalty and supporting management. It might become a target in itself to satisfy management and thereby safeguarding yourself from criticism and thus feeling safer. Another consequence of this is that people will divide into subgroups, e.g. in groups for or against management.

This form of communication spreads between the employees who will easily become aloof or have power struggles between themselves where being right becomes the most important instead of understanding each other better.

Irony and sarcasm, bullying and exclusive behaviour are often seen, and you will, in general, see that the individual is primarily concerned about taking care of oneself. In this connection, it does not matter whether you are holding your ground or keeping a low profile. Both is self-defence. When several group members look after their own interests, everyone in the group drifts more and more away from each other.

The conflict level in these groups is latent, and conflicts will easily flare up and feed old frustrations and unsolved disagreements. It creates insecurity and management often handles the conflicts by introducing more rules and guidelines. Management sets itself up as a judge, and the employees appeal for help and solutions from management instead of working their way through the conflict.

Knowledge sharing and investigative dialogues can for obvious reasons not take place in such an atmosphere. It is too risky to show insecurity and vulnerability by airing doubts and difficulties regarding work. Everyone carries the load of the doubt and risks feeling inadequate compared to the colleagues. They might to a higher degree be considered rivals instead of allies.

As knowledge is power, you often see that information is selectively and strategically shared. It creates a closed line of communication where selected employees receive and share knowledge with management while others are left out.

Insecurity and hierarchies emerge when we do not have the same access to knowledge as other colleagues. Not only the staff is underinformed. Management ought to expect that it does not know enough about what is going on among the employees.

The same might occur between departments. They see each other as obstacles hindering good results, and their perspective is reduced to what will work best for themselves. Without consideration for or understanding of the overall coherence. From time to time, it is enhanced when attention is drawn to certain people or departments instead of others, and the rivalry will increase. It is reflected in poor scores in satisfaction surveys without anyone daring to have their name associated with the poor scores. The number of sick days increases as well as the change of staff, knowledge is lost, and productivity will decline sooner or later.

The message everyone hears, or senses is that if you do not like it, you can lump it. Notices of resignation and staff cuts are very seldom a solution because they do not ensure that the dynamic that has created or maintained the problems is being addressed. If you are to understand what is wrong in such a group, you will typically look for the person being wrong instead of addressing your personal responsibility. It keeps the use of scapegoats and put even more pressure on the group and its members.

This is also how the group creates its perception of cohesive force — by maintaining an understanding of standing together against someone or something. Obstacles or direct concepts of enemies which can be everything from individuals, business partners, other departments or relatives of the ones you are working together with, etc.

If a group is stuck in this pattern, it needs external help for a longer period. Everyone has a share of interest, and no one can count on full trust or backing from the entire group to make change happen. The task is difficult because everyone has to confront their share in the patterns they have followed when surviving in the group. It also goes for the ones who have achieved special positions in the group, who will now be challenged because the patterns and roles are undesirable for growing the group.

The promising part is that no one can thrive for real in this dynamic. Many in the group long for being able to team up for better times and better ways to be together.

The decision alone about starting such a process will wake up some of the longing and competencies held back that are clear in developing groups.

Developing group dynamics

Hopefully, we all know the liberating feeling of being yourself when together with other people. Experiences with relations can be liberating and enriching and for that reason alone they strengthen your desire to be part of them. Whether you succeed in creating the developing relations depends to a very high degree on the parties’ willingness to invest, to make them important and without expecting that they can do it without an intentional and at times demanding effort from everybody.

The foundation of developing groups is created by the work carried out by the members and the work they keep doing to build mutual trust. There is a clear understanding of the fact that trust comes from daring to show yourself to others. To stand in your own light in respect of strengths, talents, competencies, limitations, doubt and vulnerabilities.

You do not necessarily have to know everything about each other’s private lives or backgrounds even though it might contribute to creating an understanding of each other’s patterns of reaction and values. What matters is that everyone is willing to acknowledge that some of the patterns in the group are drawn from other life experiences and that it might be a good idea to think about why you act the way you do in certain situations. Self-reflection is inevitable if you want to create develop.

When everyone dares to show nuanced pictures of themselves, the opportunities to feel recognised and on equal terms with the others increase. It creates a safe basis for exchanging response, both the one that you ask for and the one you get through other initiatives, without you asking for it.

One of the characteristics of these groups is that they have established good feedback structures. The structures take into account that feedback is vulnerable for both parties and that everyone must get and receive feedback. No one can safely find their bearings in a response gap, and everyone needs the inspiration to correct one’s self-perception, individual performance and thoughts in general. The response is not about being right. It is about making yourself known and provides food for thought.

In developing groups, you know that differences, disagreements and conflicts are part of any living and important relation. What matters is not that they exist but how they are handled. Because the groups are founded on trust and reciprocity, conflicts are not considered as something that threatens the relation. They are more considered as something that develops and strengthens the group over time. The conflicts do not always have to be solved, i.e. you do not have to agree on how to do it going forward and most importantly you do not decide on who was right or wrong or who was responsible for the conflict.

It is often sufficient to formulate the conflict and that both parties are able to listen to each other’s views or needs. The mutual understanding it results in, will in itself influence how you act going forward.

Management does not get involved in the conflicts very often. Management might get informed about the conflicts, and as an employee, you know that leaders are available for sparring, but people often deal with the conflicts themselves. There is in general an openness to differences, and no one, therefore, has to feel that he/she has to sense or guess what is going on. As conflicts — especially before being openly addressed — might affect a group’s general mood you feel as a colleague welcome to ease the dialogue by asking or directly encouraging to have an issue addressed to move on. In some of our time’s more visionary workgroups, it is a recurring event at meetings to formulate these tensions, both minor and major tensions or obstacles so that they are always addressed openly and early.

The relation between employees and leaders is a reciprocal relationship. You make sure that you know where you have each other. The obviousness existing in the entire group also exists in this area. The tone is informal, and there is easy access for everyone to all relevant information. In addition, it is natural to participate actively in discussions or decision-making processes. Leaders often provides sparring instead of directives, and there is high trust in people’s ability to act responsibly. From making decisions, to own up to the necessary mistakes you make as you go along.

There is therefore less focus on control and regulation than in deteriorating groups where the relation between the leader and team members is often dominated by rules and control.

Many structures and relations are looser and more flexible than you know from the other groups. It is a result of the understanding of the fact that firm structures limit the creativity and opportunities for development. It is a result of being curious or desiring to test other possibilities for collaboration and approaches to work.

Even though it might be annoying to break up good partnerships, the benefit of building new ones is bigger, and it does not diminish the importance of previous partnerships. The point is that you are aware of the fact that you are working on achieving more contact with your colleagues and thereby discover how to use each in the best possible way.

This also goes for taking the initiative. The point of departure is always to appreciate initiatives and as far as possible test them in practice. It adds to the feeling that innovation can come from within and that your workplace and group of colleagues are diverse and will not run out of opportunities. The opportunity to be able to develop in new ways increases the sense of being connected to your workplace and reduces the need for job changes.

The cohesive force existing in these groups is created by the collaboration’s present qualities and the way you confirm the relations during the workdays. Having a history together creates value, however, the present time will always be most important.

You can say that developing groups have high resilience due to their interactions and dynamics. It helps them soften the effects of the work pressure they are under, both individually and collectively. By e.g. having a routine with everyone checking in at meetings and giving a short status of own actual well-being and level of engagement. If you do this regularly, the risk of issues suddenly appearing that have been a burden for a longer period for someone is reduced.

Even though these groups are working well and are self-regulating, a periodic review or supervision from an external consultant will help the group spot areas that no longer fit their purpose or need some attention and enable the group to continue its development spiral and growth.